Thursday, April 23, 2009

TOD and the Hood

Fast forward to today. There has been a push to reverse the trend of auto dependent neighborhoods and reclaim the streets for the pedestrian. But in order to make a more walkable neighborhood, developments and land uses must be clustered together or even stacked together to reduce the number of trips a resident, shopper or worker would have to make by car or transit. Across the country TOD has had tremendous effects on suburban commuter stations and on large redeveloped greyfields and brownfields. These large TOD projects which either built around new transit stops or redeveloped large swaps of acres and parcels have created a sense of place, a sense of community and ultimately a destination.

If TOD can work in the suburbs, it can only be just as successful in cities, where the infrastructure and transit is already place, right? Well…not so much.

Redevelopment of any kind can be…difficult. So difficult and expensive that it can scare developers away. Besides cutting through government red tape and most likely changing zoning laws to accommodate TOD, developers have to seek out and buy out every parcel, deal with community groups, clean up the site and the prove to bankers that this risky inner-city development is just as stable for a loan as a new development in the burbs. Mind you searching out deeds is tedious. I once did a title search for property in Philadelphia that still showed former President William Harrison as the owner. So redevelopment can be very tough but it can be done…if done properly.

Now there are two kinds of TOD projects in inner-cities. Those that succeed and turn a profit and those that fail miserably while blowing hundreds of millions of the tax payers dollars. I’ll first cover the latter because there are a lot of failed TOD’s. In fact some planners will argue that most of the failed TOD projects were not TOD at all. They will tell you that they were really Transit Adjacent Development or Transit Related Development but whatever they were they did not implement all of the criteria needed for a successful TOD. This is all very true. Many critics of TOD (who deride it’s costs) point out the failures of Transit projects that were not really TOD at all.

When planners point out successful models of TOD from across the country, they all employ the same techniques of TOD planning which seeks to create an almost 24-7 living-working transit environment. But what planners often do not point out is that inner-city TOD projects all share one similar trait in common…instant gentrification. As I have stated in posts before, it is really difficult to build for a low income community who by the way are the ones who will use transit the most. This problem is compounded if that same neighborhood is a transitional neighborhood aka “a neighborhood that doesn’t matter” when trying to plan for the needs of the existing residents. So while a great new half a billion development is going to go up in a low income neighborhood to take advantage of it’s great infrastructure, almost none of the neighborhoods needs will be addressed in the new plan.

With so much funding, borrowed money and reputations on the line, developers are seeking to turn a large profit to offset massive debts. Ad for government officials the opportunity to completely revitalize a struggling community into a thriving commercial hub which will dramatically increase revenue and population is all but a not brainer. The consequences of potentially displacing an inner-city community certainly are not enough to outweigh new construction, jobs and growth.

So what happens to the community? Well it means neighborhoods stores and shops will now be replaced with national chain stores that are found in the suburbs to entice the young middle class to move back into the city. Which means the small grocer will be replaced by a Whole Foods. The coffee and doughnut shop will get replaced by Starbucks. The corner liquor store will get replaced by an upscale liquor store that sells mostly wine. The Chinese Food spot will get replaced by Quizno’s. So even if the existing residents do not get pushed out by rapidly raising property values, they will get priced out of their everyday way of life.

What was layered inner-city community chock full of history will be replaced by bland brick suburban architecture that mimics the suburban TOD. Now something is wrong with this picture when the city mimics the suburbs to entice suburbanites about the joys of city living. But this pattern of development is occurring cities all across the nation. Once again is easier to mass develop a project then to do it incrementally by working with separate land owners. It is far easier for one developer to buy out everything and redevelop everything at once. Now don’t get me wrong, when implemented right, these TOD projects are wildly successful but I have not seen one project yet that was able to keep the existing culture of the neighborhood.

The challenge for planners today is to make TOD work for the inner-city and not only for the new proposed residents. The solution for neighborhood revitalization can no longer be bringing in a new group of higher income to make the neighborhood better. This game of spatial mismatch has to end because there is no more developmental space in our metro areas to push people around anymore. Gentrification in our cities is now pushing out the working class, who depend on transit out of cities into the suburbs while suburbanites are now moving back to downtowns and cities with the choice of they want to use transit.

Lastly developers and planners must realize that people make neighborhoods and not buildings. While it is sad that layers of architectural history get removed for bland architecture that looks the same from Dallas to Boston, the razing of buildings does not mean the razing of the culture of that neighborhood and you develop the land as if it were a clean slate. And simply reclaiming some past vestiges and relics of the neighborhood or renaming new buildings and streets after former residents does not continue the legacy of that neighborhood without the people. While as planners we will always plan for the future to make better neighborhoods, we must always remember to plan for the needs of the people and not to the needs of a concept or theory.

Thanks for reading!

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

Transitional Neighborhoods a.k.a Neighborhoods that don’t matter

So as a planner how do you tackle a neighborhood that has real issues but will receive no funding to address those issues and generally lacks community support? The burden or working class or working middle class neighborhoods is that they often work the hardest to support themselves and their families. If there are no fires within a community, the issues of today will be put on hold until they become the problems of tomorrow.

Not that residents of poverty stricken neighborhoods have more time then the working class but when your personal safety is always in danger, you will make time to demand a better quality of life. On the opposite end of the scale, middle class neighborhoods often have the most luxury of time due to having more flexible jobs and more active retirees. As a planner the neighborhoods that you deal with the most are the ones that are the most active, which tend to be lower class and upper class neighborhoods. All the other neighborhoods, usually transitional neighborhoods are often overlooked.

I grew up in one of these transitional neighborhoods. At one point the issues of the neighborhood became problems and planners stepped in to prevent the neighborhood from having permanent systemic problems. Fortunately at the time the last legs of the neighborhood association was still kicking to grab the attention of planners. Today, the association is almost non-existent and with no fires in the neighborhood, the direction of the community seems to be blowing in the wind. Since government intervention is often complaint and community response driven, government is very reluctant to step in plan for the needs of a community without having dependable sources in the community.

As planners we cannot force our ideas on communities. We tried that in the 1950’s through 1970’s. It was called Urban Renewal and it didn’t work for residential communities. So if no one is crying for help in these neighborhoods, how could you knock the city for focusing on other neighborhoods since we know the city has bigger fish to fry. It’s hard arguing to the city that they need to focus on the streetscape of one of its main streets when other city neighborhoods are on the losing end of the war or drugs.

While it is understandable that the city with it’s limit resources has to focus on problem areas and protecting it’s middle class tax base, it’s hard to swallow that they have to do this by ignoring all their other transitional neighborhoods. As these neighborhoods goes, the city goes. These transitional neighborhoods are where the bulk of the city lives. If they continue to be overlooked then so will the city. And if these neighborhoods feel that they do not matter then the same will be felt of the entire city.

A structural change needs to occur to make all neighborhoods voices be heard. How do you get a community to be heard when it does not speak? Well, I’m not sure. But if you have a answer, I would be interested to hear from you.

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Subway Art: 25th Anniversary Edition

During the 1970s and 80s, photographers Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant captured the burgeoning New York City graffiti movement. 25 years and more than a half a million copies later, Chronicle Books is happy to offer their book Subway Art in a large-scale, deluxe format. Learn more at http://chroniclebooks.com/site/

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

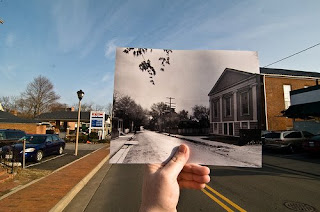

Looking Into the Past

Loudoun Street, Leesberg, Virginia

King & Martket Streets, Leesberg, Virgina

Union Station Square, Washington DC

Ellicott City, MD

Main Street, Ellicott City

Sunday, April 12, 2009

Tales of a City Planner

Recently I gave a presentation to a graduate class of future social workers about the rigors of community planning and organizing. Before I began explaining the current ins and outs of planning, I first explained why I choose planning as a career. You maybe surprised to know that many planners in planning offices do not have planning degrees. Whether it’s a good or bad thing to have people from various related fields giving different perspectives, I don’t know. Most people do not grow up dreaming to review development plans and organize monthly community meetings. As a kid, I was always fascinated by cities and always loved gazing at skylines. I had no clue of what a city planner did. I wanted to be an architect.

My dream of being an architect began with legos. Every year a group of architects would hold a design workshop with legos during Baltimore’s Artscape festival where I would help build castles, ships, towers, you name it. As I got older I volunteered with the local architects to help run the lego workshop. Those same architects gave me my first of many internships in high school, which led me to major in architecture at Temple University for two years. To come full circle now, I now review the architectural plans of those same architects as a planner who I met helping kids play with legos as a teen.

It was at Temple University that I grew a deep appreciation for cities. Temple was an urban campus right in the heart of inner-city Philadelphia. I was a kids from an inn-ring suburb and while I had visited Philadelphia dozens of times because my family was from there, I had never lived there. It was an eye opening experience. The big city allowed me to experience the new cultures and neighborhoods, the subway and el trains, lively and crowded downtown streets…and great poverty.

My University was in a neighborhood that had been in blight for over 50 years. In fact, the building my studio building was in was across the street from public housing. The studio space had the top floor in a nine story and from every direction that you looked past the campus, there was a mile or more of blighted neighborhoods. I really liked being in architecture, it was my dream. But studying how people feel and perceive space seemed trivial in the face of abject poverty that was in front of us. No matter how the spaces of the buildings of across the street where designed they were never going to feel safe.

I could not get past the fact that as future architects, if we are designing new and better spaces for people, how are we going to help the people in public housing across the street? When I asked my professor, “Who designs buildings for the poor?” The answer I got was, very few. Since architecture is still a business, there is no profit in building for the poor. Your future clients will be those with means (being individuals or institutions) and that’s who you will essentially work for.

This is not to say that all architects do is design buildings and spaces for the rich. As an intern for several architectural firms, I worked numerous public projects that would affect almost everyone from hospitals, schools, government buildings and for commercial projects intended for low income neighborhoods. Even if architects were to design pro bono for low income neighborhoods, at best all they could do is change the perception of how they felt about their neighborhoods. And while it is important for everyone to have a positive relationship about their environment, especially the poor, it is not going to bring jobs to their neighborhoods, it will not provide a better education, and it will not provide them with better skills or healthcare. Can a city planner do all these things? Probably not but at least we can educate people and help guide communities into a better direction.

So I left my major of understanding how people live and interact within their immediate spaces for a major that studies how people live and interact with their community. Both professions seek to improve the quality of how people experience their environment. The planner’s job is to help communities envision a better environment.

Well I hoped you enjoyed reading my “Johnny Do-Gooder” city planning story. Most city planners have similar tales of wanting to change their world. And while working for government can be slow and arduous, most of us still hold on to the belief that we can impact the world we live in. If you read my past tales of a city planner, then you know that changing the world I know is a lot harder then I thought. And in this line of work, it is very hard to measure any discernable success or to gauge how much of an impact you really have on your community. But all I can do is learn from the mistakes from the past so I can help plan a better tomorrow. And from these blog posts, I hope that any future planners can learn from my mistakes.

Thanks for reading!

Tuesday, April 7, 2009

Tales of a City Planner

Theory vs. Reality

One of the coolest things about my profession is planning theory. Studying how people live and interact with spaces has always been fascinating to me. Planning theory is an open conversation that almost anyone can have about how they experience the urban environment. You do not need to be a City Planner to enjoy Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. You also do not need a PhD either to discuss planning theory in depth. As one former co-worker told me, “this aint rocket science.” But the application of planning theory to the real world is…complicated.

One of the new theories that is all the rage in planning right now, is New Urbanism. To give you a quick summary of New Urbanism, it is the application of how main streets used to be planned, focusing on walkable streets and designing buildings with a pedestrian scale. New Urbanism seeks to replace the strip shopping center with large parking lot for a main street that pulls buildings closer to the street for easier pedestrian access. In a nutshell, New Urbanism seeks to create a sense of place.

As a planning theory, New Urbanism sounds great, what planner wouldn’t want to implement these guidelines to create walkable, auto-independent neighborhoods? What planner wouldn’t want to chuck their 300+ page zoning code for the simplicity of New Urbanist principles?

Well, the ultimate goal of New Urbanist principles is to help create a simple code that encourages land uses that we want to see instead of matrix of prohibited land uses, the process of determining that code is not simple at all. As life would have it, in trying to reduce the number of regulations in the code, applying New Urbanist principles can actually increase the regulation of land.

How can that be? Obviously some planner must be doing something wrong. Well when applying new urbanist principles many agencies create several standards of aesthetic design of how a building must look and how it is placed on the site. If a developer and property owner cannot conform to the new principles, then they risk having their building permit rejected. The trade off for the developer is that decisions on aesthetics are no longer made at the whims of a planning board and agency and for the public, planning decisions would not longer be done in a piecemeal fashion.

Sounds rather strict but fair, right? What would be the problem in creating a more consistent system on a more holistic level? The problem is that almost everything built in cities within the last 50 years was built in a piecemeal fashion…and I mean everything.

Streamlining sidewalk widths, I discovered there were over 10 different widths within my plan boundary (in fact some blocks had multiple sidewalk widths).

Regulating the distance of lampposts for better lighting, I discovered there was no rhyme or reason for the existing distance between lampposts.

Planters, everybody is going to make the planer the same size right? Wrong, I discovered my plan boundary had multiple planter sizes.

Awning size, how do you determine the correct size and position when every other store has different size, shape and color?

So what’s your decision? What arbitrary number do you choose to sync your new urbanist principles with existing conditions and be able to justify that number which will surely disenfranchise some property owner? Remember, these numbers have to hold before the critical eye of development attorneys. Complicated, right? And this was the easy stuff, I’m not even getting into the major details such as limiting building height, parking restrictions, reducing street widths and pre-determining building placement on lots.

While new heights and distances maybe arbitrary the existing dimensions of a piecemeal town or study area are not. Most of the times there are several concrete reasons of why there are different sidewalk widths of a town. In many cases, government may have mandated changes at the time of development or permit. Why does this matter? Well the most successful block in your town or plan boundary may employ none of the guidelines of your new urbanist principles and may have to be redesigned to meet the new standards. Or your town of plan boundary may include an historic district right smack in the middle of an area, planners have highlighted for increased density.

What do you do? If you force new regulations on the most successful block and historic district you will most likely destroy the sense of place that you were trying to create. On the other hand exempting the two areas will make your overall town or plan boundary inconsistent. What was a simple planning matter will now become a major political battle in which major constituents will let their opinions be heard to local politicians who must make that call. The argument of who is better equipped to make a major planning decision, the planner or the politician will be left for another blog post.

To repeat my former co-worker, “this aint rocket science.” However, planners are left to make a series of judgment calls of critical importance. Some judgment calls are easy, while other calls are complicated and will have unforeseen consequences for years and maybe decades to come. I hope you have enjoyed reading the complications of implementing planning theory. For any planner reading this, I know you can sympathize and I would like to hear your comments. For any planning student, I hope you learned how complicated implementing theory is and for everyone else I hope you learned more about the city planning process.

Thanks for reading!

Facebook and City Planning

Let's be honest how many of you read the updates of your local county or township's websites or sign up to receive e-mail updates?

Enter Facebook, the social network with over 200 million members worldwide, the majority of which are in the U.S. The site which connects social networks and old friends is now being used by community associations and government agencies to draw people, specifically young people to participate in the planning process. For many associations, agencies and even politicians, creating a facebook page has been a tremendous success. In Evansville, Indiana, the local Metropolitan Planning Organization has created a page displaying photos and facebook surveys. The Evansville Courier reports,

"Locally, Mayor Jonathan Weinzapfel has a Facebook page where users can read his 2009 State of the City address or find out where the next Traveling City Hall program is located. Vanderburgh County Sheriff Eric Williams uses Facebook as a resource to promote department activities and to help solve crimes."

Recently I attended a community meeting where the association was organized entirely through facebook. Instead of creating a community association website, all activity was moved to facebook where agendas, photos and other notes where posted. The association which had just been formed months earlier, had a tremendous showing for it's first several meetings. Not only did the word get out about the meeting throughout the neighborhood but the association captured the elusive 25-35 year olds who very seldom come to meetings. This is an example of facebook producing real results for a community meeting.

Unfortunately in many offices, Facebook is either prohibited or blocked, preventing the possible use of promoting agency agendas and meetings. Hopefully in the future, government will see the power of Facebook and begin seeing the website as a tool for community outreach instead of just a social network site.

Thursday, April 2, 2009

David Simon - My Baltimore

David Simon, the creator of The Wire, sat down at Werner's to talk about how the charms and idiosyncrasies of the city inform his work and the "love letter" he wrote to Baltimore.

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

Top 10 Largest Cities Observation